The Struggle for Muslim Reservation in India: A Historical Overview

Muslim Reservation in India has been a complex and evolving issue. While Islam, as a universal religion, does not endorse a caste system, Indian Muslims have developed caste-like divisions based on their professions. Despite maintaining uniformity in religious rituals and practices, these socio-economic divisions have led to distinct identities within the community.

The first recorded instance of profession-based castes among Indian Muslims appeared in the Bengal Census of 1901, followed by subsequent Censuses in 1911, 1921, and 1931, which confirmed their prominence. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Indian Constitution, remarked on this phenomenon, noting that while Islam promotes brotherhood, caste distinctions persisted among Muslims.

Research indicates that many lower-caste Muslims were converts from Hinduism, who, despite embracing Islam, remained economically disadvantaged. This socio-economic stagnation, coupled with neglect by the British regime, particularly after the 1857 revolt, exacerbated their plight. The rise of an English-speaking Hindu middle class further marginalized Muslims, as highlighted by the Indian Education Commission’s report in 1882.

The introduction of English education left Muslims unable to compete with Hindus for government jobs, a trend that pushed them into the category of Backward Classes. This status was recognized by a committee in the Princely State of Mysore in 1918, which introduced quotas for underrepresented BCs, including Muslims, in public services. By 1925, the British had also provided reservations for Muslims in government jobs.

The Government of India Act of 1935 extended reservations to Muslim castes alongside Scheduled Castes (SCs). However, the Presidential Order of 1950 restricted these benefits exclusively to SCs from Hinduism, later extending to Sikh and Buddhist SCs, while excluding Muslims. This exclusion was based on the argument that Islam does not recognize castes.

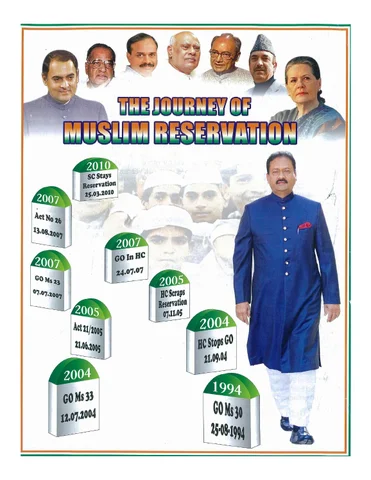

Despite the absence of strong centralized Muslim leadership and political will, the plight of the Muslim community was occasionally highlighted by socio-religious and political leaders. However, the demand for Muslim reservation did not gain significant traction until 1989, when Mohammed Ali Shabbir initiated efforts in Andhra Pradesh. His prolonged struggle faced resistance from religious leaders, who argued that Islam had no castes. Nevertheless, Shabbir succeeded in convincing the community to seek reservations for socio-economically weaker sections among Muslims.

After nearly five years, Shabbir persuaded the Congress government to include Muslims among 13 other castes eligible for reservations. However, the quota was not immediately decided, and a Backward Classes Commission was constituted to determine the specifics. The Congress party lost power in 1994, and the subsequent Telugu Desam Party government showed little interest in advancing the Muslim reservation issue, leaving it in abeyance for nine years.

The Congress party’s return to power in 2004 saw Mohammed Ali Shabbir inducted into the cabinet of Dr. Y.S. Rajasekhara Reddy. With strong political will and a clear action plan, Shabbir Ali ensured that the Congress fulfilled its election promise of Muslim reservation. Within 58 days of coming to power, the Congress government issued a Government Order (GO) granting five percent reservation to the Muslim community.

Though the GO was challenged in court and its implementation awaits the Supreme Court’s final judgment, Mohammed Ali Shabbir’s efforts have made Muslim Reservation a reality. Thousands of Muslim students have since gained admission to medicine, engineering, and other professional courses due to the four percent reservation. Similarly, hundreds of Muslim youth have been recruited into government jobs, and political reservations have increased Muslim representation in grassroots-level elected bodies like Gram Panchayats and municipalities.